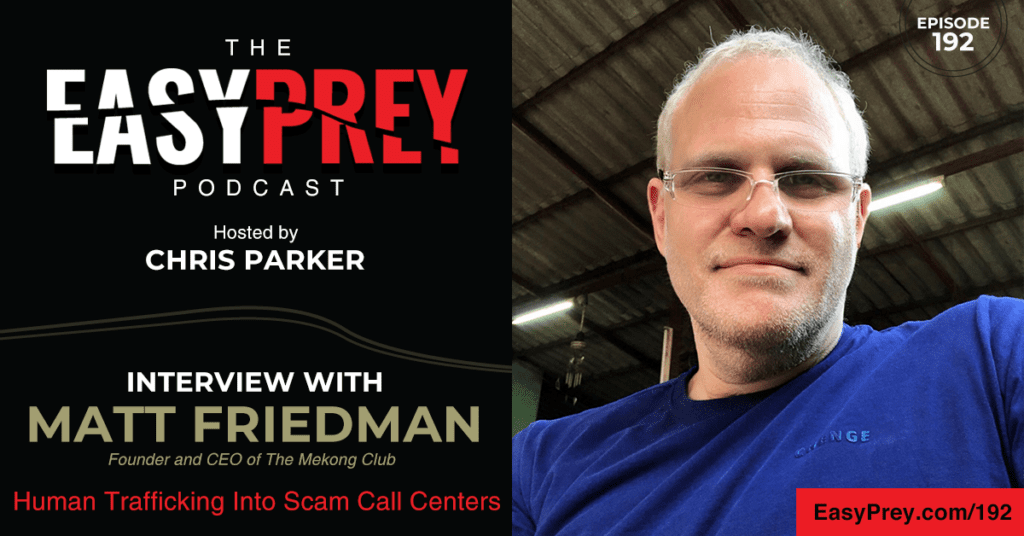

It’s hard to imagine finding a job, advancing into a second interview, they send you a ticket to their overseas office, only to find out that you’re about to be trafficked into a life of forced labor while they threaten your family. But this is happening all around the world today. Today’s guest is Matt Friedman. Matt is an international human trafficking expert with more than 35 years of experience. He is the founder and CEO of The Mekong Club, an organization of Hong Kong’s leading businesses which have joined forces to help end all forms of modern slavery.

“Awareness is essential. People need to know about this. I’m often surprised about how little people know about human trafficking.” - Matt Friedman Share on XShow Notes:

- [0:57] – Matt shares his background and the extensive experience he has in this field.

- [2:09] – Matt explains some of the terrible situations that he has seen in human trafficking and the reason he became an activist.

- [5:31] – Covid-19 impacted criminal activity in China. They started to trick and deceive people into accepting a job at a scam center.

- [6:51] – There are tens of thousands of people who have been human trafficked into scam call centers.

- [9:12] – A red flag is if it sounds too good to be true.

- [12:15] – Matt describes the buildings these call centers are in.

- [13:34] – In Myanmar and Cambodia, the people being trafficked into call centers tend to be citizens of other countries.

- [16:04] – The scams that they are forcing people to do are pig butchering.

- [18:20] – Matt shares some of the types of scams that they do from these call centers.

- [20:28] – In these call centers, if a person does not hit their daily quota, they are beaten and tortured.

- [22:56] – If you think that you want to have a job opportunity overseas, you need to know without a doubt that it is legitimate and have a system in place to make sure your friends and family know where you are.

- [25:21] – Matt’s organization The Mekong Club works with businesses on understanding scams and trafficking.

- [27:09] – Where does this laundered money go?

- [28:41] – The Mekong Club has a large social media presence in multiple languages and PSA campaigns to provide education.

- [31:32] – We’ve entered a time where scams are commonplace and it’s getting harder to tell what is real and what is not.

- [33:40] – If we don’t take action now, we will find ourselves in a situation that we cannot control.

- [37:33] – Share this information with other people. This is the most important step to take and right away.

Thanks for joining us on Easy Prey. Be sure to subscribe to our podcast on iTunes and leave a nice review.

Links and Resources:

- Podcast Web Page

- Facebook Page

- whatismyipaddress.com

- Easy Prey on Instagram

- Easy Prey on Twitter

- Easy Prey on LinkedIn

- Easy Prey on YouTube

- Easy Prey on Pinterest

- The Mekong Club Website

Transcript:

Matt, thank you so much for coming on the Easy Prey Podcast today.

Thank you for the opportunity. I'm thrilled to be here today.

Can you tell myself and the audience a little bit of background about who you are and what you do?

My name is Matt Friedman. I'm a person who's been working on addressing the issue of human trafficking for about 32 years. I started my career in Nepal as a public health officer working for USAID. I was there for eight years, five years in Bangladesh, and then I moved over to Thailand, where I ran the US government's programs for about three more years before eventually taking over one of the largest counter-trafficking programs in the world that focused in Vietnam, China, Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar.

I did that for six years. I founded an organization called the Mekong Club, which works with the private sector to address the issue of human trafficking.

What initially, 30-plus years ago, got you involved in this field?

As part of my public health work, I had the HIV/AIDS portfolio. We were finding girls 12-13 years old, and we couldn't understand why they were HIV-positive. This is a very conservative culture. We went to go and interview them.

We pretty much heard the same story over and over again. It went something like this: A human trafficker would go into a village, flashing a bunch of money around saying he's looking for a wife, find a young girl, go to the family, befriend them, and then eventually marry the girl. After that, he'd say, “I'm going to take your daughter to Kathmandu, and I'll be back in three months.” But instead, he goes to Mumbai, India, to the red light district where the brothels are.

He sells the girl to the brothel. He basically hands the wedding pictures over to the madam and goes back to Nepal to do this again and again. The madam goes to where the girl is sitting, waiting for her husband to come back. And she says, “Guess what? Your husband just sold you to me, and you're going to be with 20 guys a day everyday because I say so.” Imagine, the girl's shock. “No, no, no, my husband loves me. Where is he?” “He's gone. He's not coming back.”

When many of the girls hear this, they say, “I will kill myself before I do those shameful things.” The madam then takes out the photograph for the wedding and says, “I'll shoot mom, your dad, your brother. You hurt yourself, we'll hurt them.” She's stuck in this situation.

In order to make her into a prostitute, they simply shame her. They bring in a couple of professional rapists. Over a two-day period of time, they'll rape this girl 20-30 times till she eventually just lays back and accepts what happens to her. She will then be on the line. She will be with 20 guys a day for several years until she gets what's called Black Eye, where she's so depleted physically, emotionally, spiritually, nobody wants her, so they throw her out onto the street.

I was hearing this story over and over again, but I didn't understand the evil of it until I actually went to those brothels. I was invited by the Indian government to do public health checks. I had a police officer with me. We went into one of the brothels. There was an 11-year-old trafficking victim. This girl saw this Caucasian guy, saw an opportunity, literally ran up, wrapped herself around me, and said, “Save me, save me. They're doing terrible things to me.”

I looked down at this child who was hysterically crying. I turned to the police officer and said, “We need to get this girl out of here.” He said, “We can't do that.” I said, “What are you talking about? You're a police officer.” He says, “We try to get her out, we'll both be killed.”

To make a long story short, we left. We came back with a lot more police, but of course, she was gone. I tell this story because I wasn't one of those 15-year-olds that said, when I grew up, I wanted to be an activist. I did everything I could not to be.

Every once in a while, we have a test. This was my test. After that, I failed miserably. I couldn't eat, I couldn't sleep, and I did what a lot of activists eventually do. Surrendered to the fact that now I've been exposed to this, this is what I'm going to do with my life. Thirty-two years later, here I am talking to you.

Wow, that's an incredibly powerful story. What we're talking about today is human trafficking intersecting with scam call centers. I think most of my audience is familiar with the professional call centers being run out of a variety of countries, where this is people's job to scam people out of money, and they've got their playbooks and their training. At the end of the day, they go home. You're seeing an intersection between the two where the people are not going home at the end of the day.

That's true. When Covid hit—let’s use Cambodia as an example—you had a lot of criminals who were working within the casinos. It drew a lot of Chinese people who wanted to gamble—you couldn't gamble in mainland China. All of a sudden, these centers are closed. You had all of this infrastructure and the criminal element there, but they didn't have anything to do.

They came to realize that, well, if you start asking people for money, and you give them lies and so forth, every 10th person is going to give you some money. They said, “OK, well, there are 50 of us. If we do that, we can raise some money.” Over time, they said, “Well, why don't we just hire a bunch of people and then we can double and triple or have hundreds of people doing this? We can raise even more money. We have all this infrastructure here.”

They started to go and identify Asians to see whether or not they would scam other people. Even if they paid them, these people were saying, “No, we don't want to do it. We don't feel like this is something we want to get involved in.” They said, “OK, well, let's just bring them to Cambodia, get them in the centers, and then we'll convince them.”

They started to trick and deceive young, educated people from all across Asia, from Hong Kong, mainland China, Vietnam, Taiwan, Singapore, and so forth, into thinking they were going to accept a good job where they would make something like $5000 a month. They would arrive there, they'd be picked up, and then they'd be driven to one of these scam centers.

Upon arrival, they would be put in front of a computer to scam 14-15 hours a day, every day. If they didn't make their target, they would be beaten, tortured, tasered. What we're talking about here are not just dozens of people or hundreds of people. We're talking about tens of thousands of people in Cambodia, in Myanmar, in Laos, and so forth.

Upon arrival, they would be put in front of a computer to scam 14-15 hours a day, every day. If they didn't make their target, they would be beaten, tortured, tasered. -Matt Friedman Share on XThis is a new crime, where you have human trafficking and scamming that converge together. There are two elements. The scamming. That's what you generally talk about—the scam centers, what they do, and how they hurt people. In this particular case, you have human trafficking involved to get people into the center.

How are these human trafficker criminal organizations targeting the people that they're bringing into the call centers? What's their pitch to get them to go there? What's the lie that they use?

Oftentimes, they initially started with legitimate job search engines. It would either be websites or facilities that look very legitimate. In some cases, they would take a bank name and have an advertisement that they would put on Facebook or whatever, and then the person would contact them.

They would actually even have an interview, like it was very aboveboard. They would then have a plane ticket sent to them. They would arrive with this great expectation that they're going to have this really good adventure, make some money, live out of a hotel, and all of this, only to have something terrible take place.

Another approach is the love triangle-type situation, where a young, attractive Asian woman from, let’s say, Thailand falls in love with one of these victims—at least that's what they think is happening—and she says, “Oh, let's go to Cambodia and have a little vacation together.” She sends the ticket, he arrives, there's no girl, picked up in the van, again, taken off to one of these centers.

My goodness, that's crazy. Before we continue, are there any warning signs that these are not real job offers? If the audience is listening from Southeast Asia, how do they know whether or not one of these is a legitimate job offer or part of one of these trafficking rings?

In the early days, it was pretty transparent that what you're dealing with sounded too good to be true. You should have been a little bit cautious just based on the fact they're going to take you and give you a bunch of money in a less developed country to do a job that, generally, they could get local people to do.

For example, on some of the job ads, you'd see the name of the organization. But instead of having an email address that would have the name of the organization in there, it's a Gmail, or it says something about how advertisements for other things are there. It really doesn't look like a real ad if you stopped and studied it. But a lot of young people are so excited. They want this opportunity, so they don't really delve into those types of things.

The problem is, Cambodia, Myanmar, and Laos, are now well-established in terms of these types of sites. We're seeing that it's expanding to other locations as well. We've heard of it in Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Dubai. Several countries in Africa, Mexico recently came up. This criminal model is changing.

For a while, people were saying, “OK, well, we're just never going to go to Cambodia or to Myanmar because we're concerned about that. But what if we see it in Thailand, or we see it in Malaysia, Singapore, or these other locations? Now that the model is out there, it could potentially expand.

That's exactly what we're seeing, because what these traffickers are basically saying is that it's like having an ATM machine. You get a person, you get them to sit in a chair, and they scam all day. If they don't, you force them to do it with violence, threats, and so forth. And they're just generating money and money. If it was drug trafficking, I'd take the drugs, move them, and sell them. There's a lot of risk associated with that, not in this particular case.

They're outsourcing the risk to the people that are working in the call center, in a sense.

Yes.

What is the government and law enforcement in these countries doing about it? Or are they turning a blind eye to it?

Initially, there was a tremendous amount of pressure. When this story broke about 18 months ago, Al Jazeera did an exposé on this. It's an amazing 40-minute video. I encourage anyone who is interested in understanding what this is all about. They have good visuals. They have good background information.

Generally, what happens in this particular case is you have governments that initially were putting pressure on Cambodia and Myanmar to stop these things. For a while, there were raids and rescues that were taking place.

But then over time, what was happening is the amount of profits being generated by these centers was so much that they basically were getting rich off of this. And this is the real concern. If you are able to generate so much money that you can reverse the rule of law, and human rights violations are OK, then you really have a big problem.

And this is the real concern. If you are able to generate so much money that you can reverse the rule of law, and human rights violations are OK, then you really have a big problem. -Matt Friedman Share on XLet me give you an oversight of what these centers look like. They're in these economic zones, where you'll find 10-, 12-, 15-, 10-story buildings with large walls around, barbed wired, closed circuit television, and a criminal element keeping tens of thousands of people in these scam centers basically working. You're talking about, according to the United Nations paper that came out, in both Cambodia and Myanmar, over 100,000 victims in this situation.

The governments that put the most pressure on these governments like Cambodia, generally, were able to have some impact. The scammer said, “Well, let's go to locations where people don't care about whether or not their citizens end up in this situation.” We're seeing it in Africa. We're seeing it in other less developed countries, Bangladesh, and so forth. These victims are being brought in, and nobody's putting pressure on these centers. As a result of that, it's allowed to flourish.

Are the centers, when you're starting to move away from Southeast Asia, kidnapping people fall within local populations, or is it almost exclusively trying to get people to cross borders for the “jobs?”

In this situation in Myanmar and Cambodia, it tends to be foreign people. When it comes to the new centers and other locations, I suspect in Bangladesh, you're going to find Bangladeshis being trafficked into Bangladesh centers, but we really don't know. This is a new thing, a new phenomenon. We're just beginning to hear that scamming is coming out of those particular locations.

It's important for us as crime fighters to basically understand the typology of what's happening, how it's playing out, and so forth. We understand it in Southeast Asia, but we don't understand it in the other parts because what happens is there's an evolution of change, where the scam centers in these new sites learn the weaknesses of the other scam centers—what works, what doesn't work, how to protect themselves—and then they integrate that into the new scam center approaches.

Are these new criminal organizations, or let's say criminal organizations that used to do drug, weapon trafficking, and just seeing like, “Hey, this is “safer,” let's do this instead”? Or are these new criminal organizations just being built from the ground up?

It's a combination of both. The thing about organized crime is it's actually organized. If you have a syndicate or a family-type dynasty that does criminal activities, they diversify. They start with drugs, and then they'd have girls, and they'll do something like this. They're always looking for the most lucrative approach with the least amount of risk associated with it. Up until now, there's virtually no concern about getting caught in this situation.

They're always looking for the most lucrative approach with the least amount of risk associated with it. Up until now, there's virtually no concern about getting caught in this situation. -Matt Friedman Share on XThe interesting thing about what we were seeing in Cambodia is as the call centers were being raided and they were rescuing people, then they would just basically move to another location. Along the Myanmar border, you have no-person’s land because you have the rebel groups and so forth. The government doesn't have any access there. That's a great location for a scam facility, because nobody can go in and do anything associated with these centers.

Got you. What types of scams are they often operating out of these call centers?

It's the typical pig butchering scam. The terminology pig butchering is you basically take a pig, you fatten it, and then you slaughter it. It's the same idea when it comes to scamming.

As a typical example, what they'll do is, let's say a young woman reaches out to a 55-year-old divorced guy. He's by himself, he's lonely. She does an accidental correspondence. “Hey, Michael. How are you doing?” The person goes back and says, “I'm not Michael.” “Oh, I'm so sorry. My name is Michelle. How are you doing? You're so nice. He was so nice to respond and not get angry with me.” That generates into a conversation.

That, over a couple of weeks, becomes a friendship. They're going back and forth, and they're talking with each other. He has access to this young person who is helping him to feel good about himself, and then she'll say something like, “Oh, I made $5000 on crypto.” “Really? How did you do that?” “Oh, well, let me show you.”

She brings up the screen, and you can see the screen. She puts $5000 in. The next day, it's $10,000. She's controlling all of that. She says, “Why don't you try it yourself?” So he puts $5000 in, and then the next day he gets $10,000. She says, “Take the money out. Go ahead, take it out. You can see this is real.” He takes it out. She says, “Let's do it again.” Put $10,000 in. Boom, $20,000, and take it out.

That's all about developing this sense of trust. Another week goes by, nothing. Then she says, “Oh, my gosh. Great deal. There's a coin that's going to come out. If you put a million in, you'll get $5 million back. It's got to be at least a million.” “I'm sorry. I don't have a million. I have $750,000.” Take that, you know it's real, because you had this experience. Borrow the other $250,000 from your friends, family, and so forth. Boom.

He puts the money in. The next day, it's $5 million. He says he tried to get it out. “Oh, no, no, no. Sorry, you can't take it out. The US government has these regulations and so forth. You've got to know the client, and you got to get all this information.” He keeps adding and adding till it looks like there's no more money, and then it terminates, and you'll never see that person again. The story, you probably talked about it many, many times with your audience.

Another very scary approach is in India, where you have an ad that will say, “If you want to borrow ₹14,000 at a very low interest rate, press this. It will give you access to this, and the money will be sent to your whatever money exchange account is.” They do it not realizing that that person now has access to that person's phone, so they take all the phone information.

When they try to pay it back, they say, “No, you have to pay more. You have to pay more.” They don't. They start reaching out to the family members. They start using AI to have that person's face on a naked body with somebody else. They'd say, “We're going to show this to your family and everything.” This has resulted in a number of suicides, because in that country, there's a lot of shame associated with that type of thing.

The scammers continue to get much more creative in the way that they go after people. With artificial intelligence being what it is, the chat scripts are getting better, the imitation websites look so real and so genuine. They have the code so that the person presses one thing from a legitimate site that brings them into this other illegitimate site thinking they're in a good site, protected site, only to eventually have themselves be hacked over time.

That's awful. I guess we’ve got both sides of this. You have a rich victim and then usually a poor victim who's being forced into the call center. What's the strategy or angle of trying to work to reduce this type of crime?

Let's talk a little bit more about the victims. Generally in human trafficking, there are 50 million people in modern slavery. Many of the traditional victims in the past had been migrants in lower socio-economic circumstances. In this particular case, you have kids from families that are affluent, middle class, and so forth. It's a completely different dynamic.

I want to emphasize the one element of this that really is quite concerning, and that's the violence associated with it. If you are in one of these scam centers, and you don't meet your target, and one side, it was $14,000 a day that you had to give, you're going to be beaten, you're going to be tortured, you're going to be tailed, tasered. Terrible things are happening to these people. In fact, you can see these videos on Telegram. They’re right out in the open.

As a result of that, you have these people who have never experienced any kind of trauma, all of a sudden in this high-trauma-type situation. If they're really not generating money, they often sell them between these scam centers. In fact, again, on Telegram, you can see, I have three Bangladeshis, two people from Thailand, and this is the amount of money. Buying and selling right out in the open.

If that doesn't work, then basically they try to sometimes sell the person back to their family, $20,000-$30,000. If they can't do that, sometimes these people are actually killed. They videotape the killing and then basically sell the videos to people who are interested in what's called harm core, where basically you pay to see violent things take place to people. You have this horrific situation where victims are put through hell.

Those who get back, in some cases, when they get back, they are actually arrested. They're arrested because they scammed people. Let's say it's a Hong Kong person, they scammed somebody in Hong Kong, not because they wanted to. It's to basically prevent themselves from having terrible things happen to them, but there are no laws that basically protect the victim from the work that they did that was illegal and so forth.

In the human trafficking world, there are laws that basically say, “If you are trafficked into prostitution and it's against the law, then you get to get out of jail free card,” but there's nothing like that associated with this.

How to prevent something like this? First of all, I think awareness is essential. People need to know about this. I do talks all over the world on human trafficking, and I'm often really surprised at how little general knowledge is out there. But when it comes to something very specific like this, very few people know about it.

The other thing is that everyone is really upset and angry with the scammers for what they do. But in this particular case, you have a person who is a victim of forced scamming their victims, your victims. How do you reconcile that situation, where a person is forced into this type of situation? We haven't really come to terms with that.

If you think that you want to have an opportunity overseas in the form of a job, and it sounds too good to be true, it probably is. -Matt Friedman Share on XIf you think that you want to have an opportunity overseas in the form of a job, and it sounds too good to be true, it probably is. Even if you check it out, have interviews, and everything else, you really need to have some type of system in place to understand whether or not if you arrive there and something bad is about to happen, you can alert your community that there's a problem. There are emergency apps. You just press a button, and it gives the geographical code, where you are, and sends a message out. But this is a new world that we're into.

If you're in a foreign country far away from your friends, family, and people who have resources to do something, it's not like there's the neighbor down the street. It's a lot more complicated to get resources to do something. What pressure is on governments to do a better job in combating this?

I've had discussions with government people on both the human trafficking into scam centers in the scams themselves. Let's use the United States, for example. There are a lot of resources that are being used by different agencies to address the scamming side of things. But when I had conversations about human trafficking into scam centers, there was no understanding of this being a phenomenon that they had heard about. They don't really know what to do with it because the scammers are in Asia. How do you address that type of situation?

I suspect what will happen based on the recent United Nations report that came out that talks about this, not the scamming, but the human trafficking into scamming, that there will eventually be multi-stakeholder meetings where governments will start coming together, and they'll debate and discuss what needs to be done. But that process is slow.

In the interim, as these scam centers begin to take hold at different locations, and as the money generated from the scam centers becomes so obscene that they can basically insulate themselves, that's really what my concern is more than anything else.

I work for an organization called the Mekong Club. We're based in Hong Kong, and we work with the private sector to help them to understand the issue of human trafficking and what they need to do to address it. We work with the banks, the manufacturing companies, the retailers, the hospitality, tech world, and so forth.

The nexus for us in terms of this is the fact that scamming has a potential impact on the banking world. We have developed a working group in Asia to focus on this and another one in North America, because we're really trying to do it with the financial institutions to say, “You guys need to be the standard bearers for helping to raise awareness about this particular topic with governments, because we really need to act now.” This is one of those blinking light, DEFCON seven-type things, where if we don't address it now, it's just going to get so out of hand that we're not going to be able to contain the beast that's developing.

This is one of those blinking light, DEFCON seven-type things, where if we don't address it now, it's just going to get so out of hand that we're not going to be able to contain the beast that's developing. -Matt Friedman Share on XWhen you're calling out the banking sector, is that because in some sense, the money has to flow through somewhere so they have the most opportunity to intervene?

There are a couple of different aspects of this. We're talking about crypto, and a lot of banks don't have direct involvement with crypto. It's a separate mechanism. But if you have a person who has a half-million dollars in your bank, and they haven't touched it for 20 years, and all of a sudden they're taking out $50,000 increments, that's a red flag for something possibly happening. It's a red flag for a person making potentially bad decisions and so forth.

The other side of it is the money-laundering side. If this money is generated in huge amounts, it has to go somewhere. We saw recently in Singapore, there was a case where they identified almost a billion US dollars worth of money laundering in the form of real estate, luxury cars, luxury goods, cash, and so forth. That money laundering, if a bank has any of that money in it, they're going to be fined.

There was a bank in Australia that was fined $1.3 billion because they allowed online sexual exploitation of children to take place. There are other bank fees. The problem is the reputational side of it.

Let's say that you had a bank that had a 100-year legacy of trust and honesty, and all of a sudden, human trafficking and the bank name come together. Wow, that has a devastating impact on that particular business.

The banks are stepping up. They are looking at typologies. They are looking for red flags. They are beginning to focus on this. I think with the banks, the regulators, and the governments, which are combined at this particular point, then we could have some momentum in addressing this.

Got you. If I'm not the person in Southeast Asia looking for a job, but I'm here in the US, and I want to help, how can I help? What can I do? Screaming and yelling at the person who's trying to scam me is not particularly effective. What can I do to help?

The organization that I run uses volunteers. We set up a campaign about eight months ago. What we're doing is going onto social media in multiple languages to alert people both to the scams and to the human trafficking into scam centers.

We are in the process of developing some public service announcements, where we're going to come up with almost like commercials that will help to incentivize people. If something looks too good to be true, don't take it. But in a very creative way, we're trying to raise some money for that particular approach. It can be in multiple languages, the way we're doing it.

We will have a website that will basically give prevention information, again, in multiple languages. When it comes to human trafficking, 90% of the material tends to be in English, but 90% of the people who need it don't speak English. It'll be in Mandarin, Cantonese, Thai, and Burmese.

Eventually, we will expand that. It will be an open-source-type thing. I'm doing a lot of presentations at schools, at banks. Corporations have asked us to come in.

People can get involved in helping with that particular process. Just talking about human trafficking in general, there are 50 million people estimated to be human trafficking around the world. That includes sex trafficking, forced labor, and so forth. Out of 50 million people last year, the world helped 108,000, which is 0.2%. That's with all the United Nations, governments, and NGOs.

Just talking about human trafficking in general, there are 50 million people estimated to be human trafficking around the world. That includes sex trafficking, forced labor, and so forth. Out of 50 million people last year, the… Share on XThe issues of our time are not going to be solved by 25,000 people like me against a half-million criminals. We as a world need to accept some responsibility. If you're a banker, if you're a risk-assessment person, if you're a communications person, if you're a public relations person, then let's set up a community so that we can collectively work on these things together. If we wait for this to happen with the governments, it may take a long time. We really need to be addressing this right now.

We don't want people waiting until it's their child that has trafficked before they get involved. We want people to get involved well before that ever even is a possibility.

And we know what's happening, where AI is able to take a person's voice and then basically do a mom-I'm-in-trouble call, where the person will get a call. “Mom, I can't talk now. If you have to send money to this, I'm going to send you a WhatsApp code. Help me, help me” type of thing.

You know it's not real, but obviously as a parent, you stop thinking rationally and practically when you get a call like that, and you go ahead and make a decision based on this. I just had somebody recently tell me that they got a simple email, and it looked like a person that they knew, and they hit the link. All of a sudden, terrible things happen to their computer.

We've entered a situation where the vulnerability of our machines being hacked and people getting into it, and then figuring out who we are and our information, and then using that, or getting our credit card information or whatever is very much a reality.

How many times do we get scam invitations on WhatsApp, for example? “Hi, I'm so-and-so. I want to be your friend.” That type of thing. We have to all be vigilant, because it will eventually get to a point where maybe you won't know what's real or not real, because it looks so real, it tastes like it's real, but it really isn't.

You're talking about the misdirected text messages. There was definitely a time that I was getting two or three of those a day. I've seen a very similar thing going on LinkedIn. “Oh, hey. You look like a very interesting person.” I'm like, “No. Trust me, I'm not that interesting.”

What's interesting about that is if you look at their profile, they always have about 30 followers. They have this pedigree of going to this great university, and I worked for this great job, but it's so lean in terms of they worked for six years, and they only have four things on their LinkedIn. It's pretty transparent that that's what it is.

I committed myself to posting every day for a year on LinkedIn on human trafficking and other issues. I managed to do 520 words a day. What it did is it expanded my network, but it also expanded my exposure to that type of thing. I was getting a lot of people approaching me.

I post on this particular issue as well. I posted a couple of days ago on this. General awareness is an essential part of the process. I just can't emphasize enough that this is one of those moments in time where we're almost at a tipping point. If we don't act now, if we don't address this now, if we don't incentivize governments now, if we don't really take action now, we are really going to be in a situation where this is beyond what we can control.

We've seen all the CEOs from the AI companies come together and talk about the dangers. This is one of those dangers that they're talking about. The fact that many of us are vulnerable to people taking our identity or somehow taking our money, because AI has the potential to incentivize people to use new systems, procedures, and approaches to get money from other people.

Yeah. Once these cartels and criminal organizations have more money than local governments, it's hard for local governments to do anything about them.

It's funny. I watched those Mission Impossible, James Bond movies, and so forth. They talk about the evil empire that exists behind the scenes. This has the potential to develop that. This is really where ours is turning into the reality of the situation, because the potential for criminal activities to be expanded significantly beyond what we've ever seen before now exists.

How does that translate in terms of this influencing political people getting into power? Elections and all kinds of other things remain to be seen, but you can, in your mind, imagine. If you have so much money that you can pretty much buy whatever it is that you want, where is the world going to go if we go in that particular direction?

That's a scary thought. I don't want to pursue that conversation at the moment.

Yeah, me too.

Are there any online resources? We definitely talked about the Al Jazeera video for people who want to learn more about this. I'll get the link from you and put that in the show notes. What other kinds of online resources should people be sharing or making them aware of?

This online portal that I mentioned; I'll share that with you and for your audience. It should be up within a week or so. It's very spartan. All it does is just gives you a heading, and then in multiple languages, what it is that you need. I would say to the audience, watch that video. Google human trafficking into scam centers so that you can generally see all the articles that are coming out related to this.

If you're a parent, alert your kids to the fact that they exist. If you're in a network, talk to your friends about this, post on this. Do whatever it is you can to raise awareness, because a big part of the process is just getting people to know that this particular situation exists.

If you have elderly parents that are not very computer literate, if they all of a sudden get an email that says your account is going to be frozen because you didn't do something, and they just get very concerned immediately, and all they can think about is, “I have to fix this thing,” so they follow the approach, and they're seeing websites, and they keep hitting the buttons, bringing them to the point where the person has access to their computer and their accounts and everything else, then that's a very serious situation.

A lot of people, again, I'm talking to an audience of people that know what I'm talking about, these scammers will go after certain prototypes, certain types of people. They're more vulnerable simply because they get scared quickly and they don't really know much about what scammers do and how they do it, so they get caught in this trap.

Education, education, education.

Absolutely. That's why this podcast is so important. It's getting this information out to as many people as possible. Get people to watch these types of podcasts. This is an essential part of the process, because until you see this, you really don't know that there's this vulnerability.

Yeah. Aware of human trafficking and aware of scam call centers, but to see the two of them intersecting is particularly disturbing.

Absolutely.

If people want to connect with you, how can they find you? And how can they find the Mekong Club?

You can list our website. I'm happy to even include my email address if anyone's interested in contacting me directly, if they're interested in learning more about the situation, even volunteering and so forth.

Awesome. Matt, thank you so much for coming on the podcast today.

Thank you for the opportunity, and I appreciate what you do.

Thank you.

YO sufrir maltrator, discriminación comentarios de odio manazas de muerte, robó de información,robo de propiedad intelectual